Curated Alpha for Traders

Get the latest news and analysis on Bitcoin mining and hashprice trading in your inbox every other week. No spam. Unsubscribe anytime.

BLOG

Get the latest news and analysis on Bitcoin mining and hashprice trading in your inbox every other week. No spam. Unsubscribe anytime.

By: Ben Harper and Matt Williams

Long gone are the days when bitcoin mining was an easy business.

Today, building a successful mining operation requires capital, physical infrastructure, computing hardware, low-cost energy, and an assortment of technical skills. Even still, miners must navigate an ever expanding set of risks to their operations, including hashrate competition, crypto-prices, rising energy costs, and government scrutiny – just to name a few.

On the revenue-side, some would incorrectly assume that bitcoin’s price is all that matters.

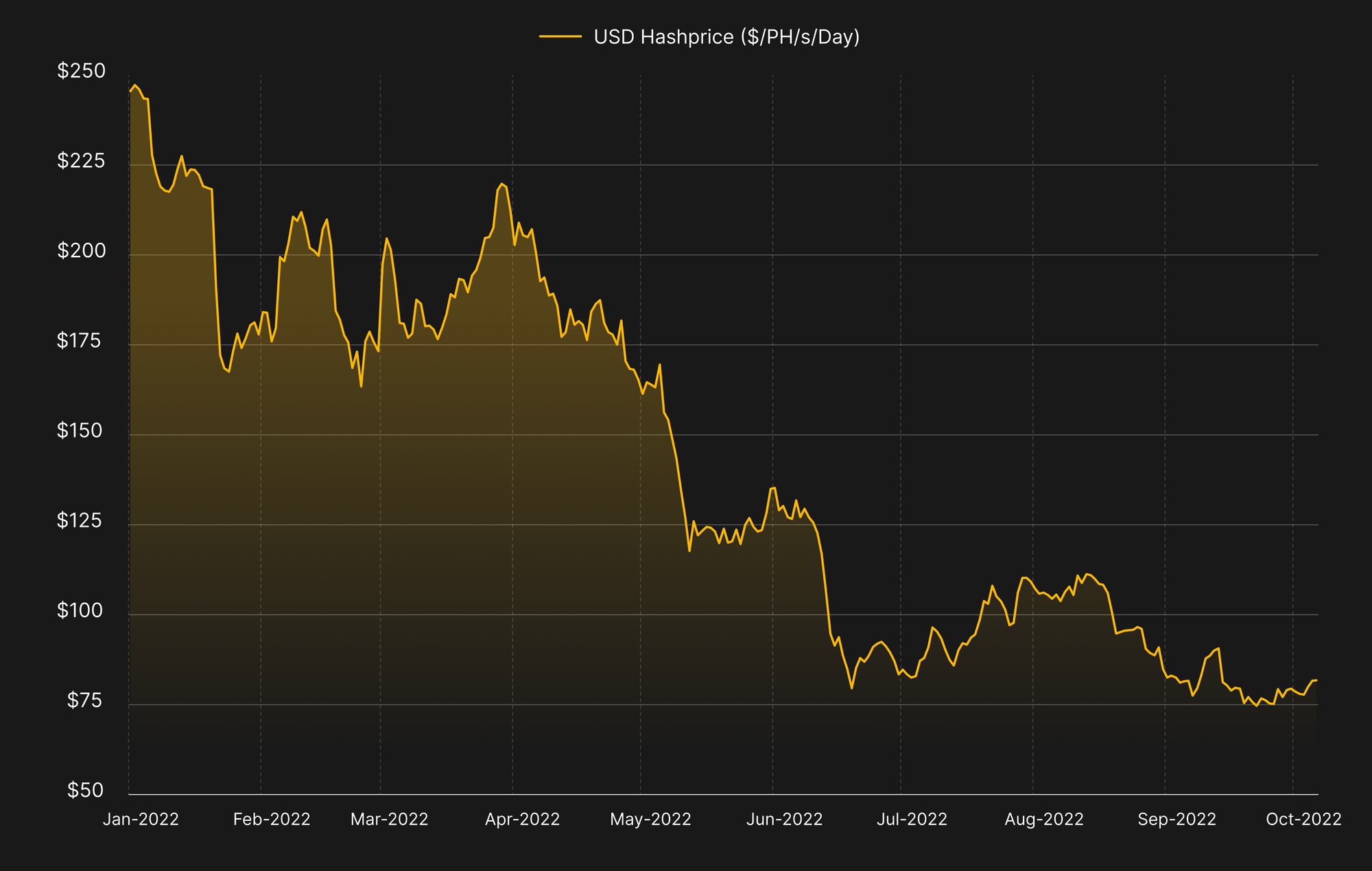

But Bitcoin miners produce hashrate. And what they are paid for that hashrate – what Luxor coined hashprice in 2019 – is a function not only of bitcoin price, but also the block subsidy, transaction fees, and network difficulty (i.e, the amount of mining on the network).

The higher the block subsidy, transaction fees and bitcoin’s price, the higher the hashprice and vice versa for lower hashprice. Network difficulty works in the opposite direction: the more mining on the network, the smaller the slice you get from bitcoin’s fixed issuance schedule.

On the cost side, bitcoin miners have power-purchasing agreements to hedge electricity prices, electricity derivatives, bitcoin derivatives to hedge their balance sheet, insurance to hedge operational risks, and industry associations to mitigate unfair regulation and taxation.

On the revenue side, miners only have bitcoin futures and a small patchwork of physically-settled, short term-duration hashrate forward options available. These limited hashrate hedging options leave many miners exposed to significant hashprice risk and make it difficult for them to build defensible businesses in a highly cyclical industry.

In other commodity markets, this isn’t the case.

Farmers use forward contracts to lock-in prices for corn, wheat, and rice crops, among others. Oil and gas producers use futures contracts, and electricity providers use power purchase agreements. Financial institutions use currency forwards, forward rate agreements, and equity forward contracts. The list goes on.

Forward contracts (or forwards for short) are the oldest and simplest form of financial derivative. Evidence of their use dates back thousands of years, to the ancient civilizations between the Tigris and Euphrates, where clay tablets were used to record delivery dates for local produce.

A forward contract is made between two parties. It typically has one of two outcomes: physical delivery or cash settlement. In a physically delivered contract, one party agrees to buy a commodity on a future date, at a fixed price. The other party agrees to deliver that commodity or asset on the future date, at that fixed price. In a non-deliverable, cash-settled forward contract (“NDF”), the difference between the fixed price of the contract and the settlement value of the underlying commodity at the expiration of the contract is paid in cash from one party to the other.

Luxor’s Hashprice NDF brings together buyers and sellers of hashrate for customizable, non-deliverable hashprice forwards. After completing the appropriate onboarding documentation, the buyer and seller of a Luxor NDF contract simply agree to the following:

Luxor facilitates the contract by matching counterparties, promoting price discovery, managing counterparty risk, providing tools for daily profit and loss calculation, and acting as the settlement agent, as the contract is settled to Luxor’s Bitcoin Hashprice Index.

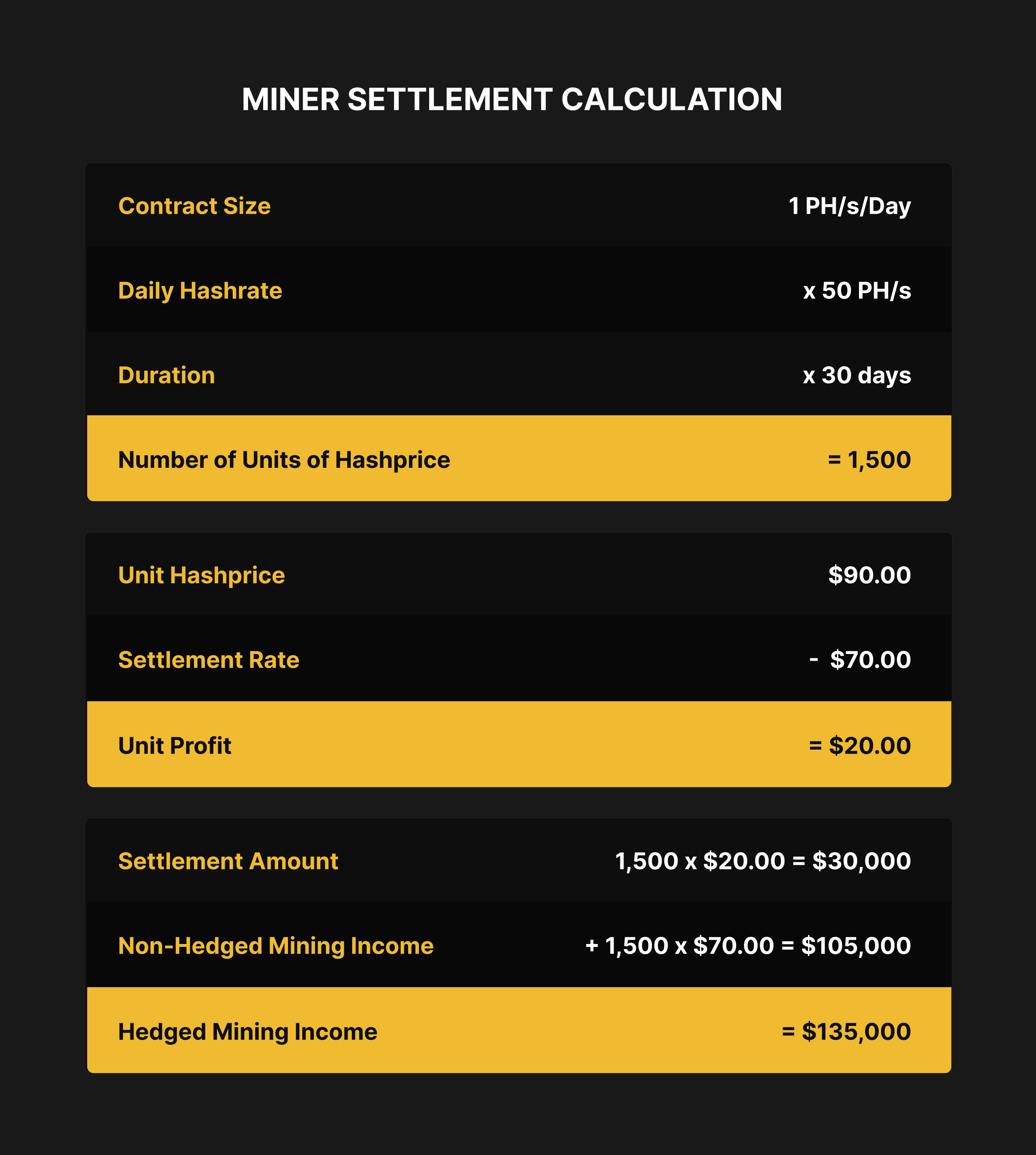

Suppose a miner has 50 PH/s of daily hashrate and wants to hedge their entire exposure to hashprice for 30 days.

The miner continues normal mining operating activities and sells 1,500 contracts (50 PH/s x 30 days) at $90.00 per PH/s/day. Assuming the miner is hashing, the NDF in this example will completely hedge (i.e., lock-in) revenue. They may also look at other products to hedge their costs.

At expiration, the settlement rate is $70.00 per PH/s/Day.

In this scenario, the miner would receive a $30,000 profit from the NDF ([$90.00 - $70.00] = $20.00 x 1,500), offsetting their lost revenue from negative movement in hashprice. Overall, the miner would receive an amount equal to selling 50 PH/s for 30 days at $90.00 per PH/s/day. Using Luxor’s NDF, the miner is able to guarantee the revenue they receive for their hashrate.

Now of course, the math works the other way around. Had hashprice moved above $90.00 per PH/s/Day, the miner would have had a loss on the contract. But, the miner would still receive an amount equal to selling 50 PH/s for 30 days at $90.00 per PH/s/day. That’s how a non-deliverable forward hedges hashprice risk.

Try out Luxor’s miner hedging calculator to play with various hedging scenarios.

Buyers of this contract are looking to gain exposure to hashrate and generate alpha without owning physical assets, while others may want to procure hashrate quickly when dealing with long lead times. Purchasing a hashprice NDF allows for temporary non-physical exposure to hashrate. Examples of NDF buyers include:

Sellers of this contract are looking to hedge hashprice risk if they are miners, hedge counterparty risk if they are financiers, or generate returns if they are investors. Examples of NDF sellers include:

Want to learn more or see the trading desk? Please visit Luxor's derivatives page.

Do you have any questions?

Please contact our support team